They’ve pulled out the big guns! The West is stunned, realizing they never saw this coming… China’s strictest export control policy on rare earth technology is here! 出大招了!西方傻眼了,還可以這樣玩…最嚴格稀土技術出口管制政策來了!

They’ve pulled out the big guns! The West is stunned, realizing they never saw this coming… China’s strictest export control policy on rare earth technology is here!

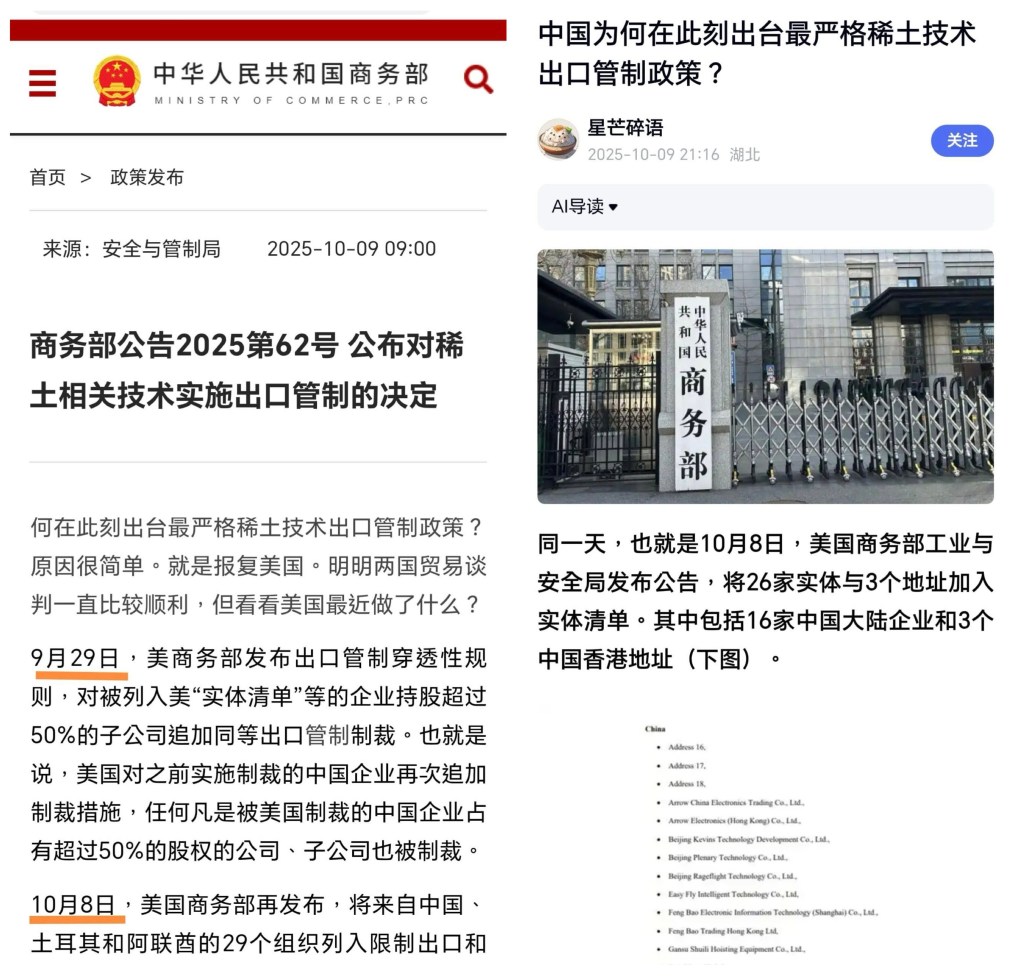

On October 9, the first workday after the National Day holiday, the Ministry of Commerce dropped a bombshell announcement: export controls on rare earth-related technologies and overseas rare earth items will be implemented.

China’s rare earth technology exports have entered an era of stringent oversight!

The most decisive move? Cutting off American military-industrial companies—Huntington Ingalls’ rare earth alloys for aircraft carriers and Flat Earth Management’s defense data systems have all been added to the control list.

And guess what? The U.S. Department of Defense just signed an equity agreement with domestic rare earth suppliers, and now China is pulling the rug out from under them.

Consider this: 70% of America’s rare earth imports come from China, with dependence on certain critical materials as high as 90%. Last year, due to rare earth supply disruptions, U.S. companies faced order delays of two to three months, and magnet prices surged five to sixfold.

Now, things have gotten even worse—even technical support is being cut off. The rare earth mining project Pakistan just negotiated with the U.S. has directly fallen through.

The brilliance of this move lies in its “surgical strike.” China isn’t just restricting rare earth exports; it’s also controlling rare earth items produced overseas. For instance, Vietnam’s newly built rare earth separation line relies entirely on Chinese technology and equipment. Now, if they want to expand production? They’ll have to apply for a permit first.

The G7 was previously considering price caps on rare earths, but China countered with a “technological chokehold.” With 90% of the world’s high-end magnet production capacity in our hands, what alternatives do they really have?

Even more impressive is the adept use of the legal framework. These controls are based on the “Export Control Law” and the “Dual-Use Items Regulations,” with rare earth technology having been listed in the restricted catalog as early as 2001.

The West often accuses “China of undermining free trade,” right? Well, now we’re pointing to the legal provisions: if you’re using rare earths for military purposes in violation of non-proliferation obligations, who can you blame?

The most awkward situation now belongs to the Norwegian expert. Earlier, he confidently claimed on television that “Fukushima’s nuclear wastewater is safe to drink,” only to be left speechless by Gao Zhikai’s rebuttal.

Now, with the announcement of these rare earth controls, Western media have collectively fallen silent. Only Trump is left shouting on Twitter about “China choking us.” But he seems to have forgotten how self-righteous the U.S. was last year when it sanctioned Huawei.

出大招了!西方傻眼了,還可以這樣玩…中國最嚴格稀土技術出口管制政策來了!

10月9日,國慶後上班第一天,商務部就發布重磅公告,宣布對稀土相關技術及境外相關稀土物項實施出口管制。

中國稀土技術出口迎來強監管時代!

最絕的是,直接給美國軍工企業斷供——亨廷頓·英格爾斯造航母的稀土合金、扁平地球管理公司的國防數據系統,全被列入管制名單。

你猜怎麼著?美國國防部剛跟本土稀土商簽完入股協議,這邊中國就釜底抽薪。

要知道,美國70%的稀土靠中國進口,部分關鍵材料依賴度高達90%。去年美企因為稀土斷供,訂單推遲兩三個月,磁鐵價格漲了五六倍。

現在倒好,連技術支援都被卡死,巴基斯坦剛跟美國談好的稀土開採項目,直接成了泡影。

這招妙就妙在“精準打擊”。中國不僅限制稀土出口,還把境外生產的稀土物項也管住了。比如越南新建的稀土分離線,技術設備全是中國的,現在想擴產?先申請許可證再說。

G7之前琢磨着給稀土限價,結果中國反手一個“技術鎖喉”,全球90%的高端磁材產能攥在咱們手裡,他們拿什麼替代?

更絕的是法律框架玩得溜。這次管制依據《出口管制法》和《兩用物項條例》,早在2001年稀土技術就被列入限制目錄。

西方不是老說“中國破壞自由貿易”嗎?咱直接亮法條:你們把稀土用到軍事領域,違反防擴散義務,怪得了誰?

現在最尷尬的是挪威專家。之前還在電視上拍胸脯說“福島核污水能喝”,結果被高志凱懟得啞口無言。

這次稀土管制一出,西方媒體集體裝聾作啞,只剩特朗普在推特上喊“中國卡脖子”。可他忘了,去年美國制裁華為時,也是這麼理直氣壯。

When Washington declared an economic war on China’s technology ascent, it assumed it held the upper hand. Tariffs, export bans, entity lists and chip sanctions were meant to isolate Beijing, choke its access to critical inputs, strangle its technological development and protect American primacy. The US believed, actually bragged, at the time, it had stopped China’s technological development in its tracks.

Yet with remarkable precision, Beijing has now demonstrated that the United States is the one more deeply entangled in – and dependent upon – China’s command of critical material supply chains.

Exactly.

China’s latest round of export controls on lithium batteries, graphite anode materials, and rare earth technologies amounts to the most significant intensification yet in the global race for material sovereignty. The measures are framed in terms of “national security,” and necessities to meet China’s obligations to not accelerate arms proliferation. At the same time, the strategic timing and scope make clear their geopolitical intent: to again expose the material vulnerability of a country that has worked tirelessly to encircle, contain and repress China, but which itself cannot easily reconstitute its own productive base.

The new Chinese restrictions announced on 9 October 2025 extend beyond commodities to include the technological processes required to make them useful. This is a deft and also an important expansion of reach from mere resource control to technological chokepoint management.This is actually what the US did to China in terms of chips: not simply the chips themselves, but the tools to design, make them–any foreign manufacturer that had a US component or a US patent somewhere in any of its machinery was constrained from exporting to China. It was as CSIS called it, “4 point chokehold strangling with intent to kill”, “an act of war”. The US is now getting a taste of its own medicine.

In terms of graphite anode materials and lithium batteries, China will now require export permits for synthetic graphite and natural graphite materials used in the production of lithium-ion battery anodes. The restrictions also cover advanced production processes, including granulation, continuous graphitisation, and liquid-phase coating. These are all key technologies that determine battery performance and durability. These technologies are essential for electric vehicles (EVs), consumer electronics and grid-scale energy storage systems. China currently accounts for over 90% of the world’s graphite anode production and dominates every stage of the lithium battery value chain.

As for rare earth-related technologies China has added a sweeping range of rare earth technologies to its export control list, including those involved inmining, smelting, separation, magnetic material manufacturing, and secondary resource recycling. These underpin the manufacture of permanent magnets used in wind turbines, electric motors, guided missile systems, fighter jets, satellite components and semiconductors. China refines nearly 90% of global rare earth oxides and produces the vast majority of neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets used in high-performance electronics.

Together, these measures strike at the heart of the clean energy, defence, and semiconductor industries. In other words, the very sectors the U.S. has spent billions trying to re-shore through the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS Act under the Biden Administration, and which are central to the Trump Administration’s vision for America’s techno-military future. (The focus on clean energy has been dropped.)

According to the Pentagon, over 78% of U.S. military systems rely on materials sourced directly or indirectly from China. Rare earths are used in everything from jet engines and precision-guided munitions to radar systems and nuclear submarine components. A disruption in Chinese supply chains would delay weapons production and maintenance schedules. The U.S. has some rare earth deposits but lacks refining and metallurgical expertise; ironically, these were offshored to China decades ago. Rebuilding domestic refining capacity could take 5–10 years and cost billions, even before environmental approvals and workforce training are considered. Against this backdrop, China’s export restrictions can be seen to be a massive boost to world peace.

While U.S. policymakers focus on lithography and chip design, the less glamorous but critical material inputs – rare earths, gallium, germanium and graphite – remain overwhelmingly Chinese. Rare earth magnets are essential in chip fabrication equipment and data centre cooling systems. Restrictions on graphite and high-purity processing technologies will squeeze the semiconductor value chain from the bottom up, affecting everything from consumer electronics to AI compute clusters. This has wide-ranging implications. Without the rapid expansion of AI capital development in 2025 (data centres and the like), the US GDP growth for the first half of 2025 would have been, according to some estimates, no more than 0.1%. Put another way, the American economy writ large is flaccid at best, and AI-related capex is keeping its head above water. Disruptions to the input supply chains needed by the AI sector will jeopardise the sector’s expansion; it will also increase costs due to supply side disruptions. The impacts of China’s restrictions are double-barrelled: they go to the resources needed for augmenting the US electricity supply sector on the one hand, while also creating bottleneck risks in the supply of semiconductors. The Wall Street AI bubble may well be exposed to the sharp needle of Chinese export restrictions.

The EV revolution in the U.S., if indeed one could even call it that, depends on a Chinese battery ecosystem that dominates both upstream materials and midstream processing. China processes two-thirds of the world’s lithium and over 90% of the world’s graphite. U.S. automakers have only recently begun investing in local cathode and anode production, but the know-how and equipment still come largely from Chinese firms. Supply disruptions will increase EV costs, reduce availability, and slow decarbonisation timelines.

In short, America’s green and digital transitions are built on Chinese foundations. Now those foundations are shifting, or perhaps worse, those foundations have simply been removed.

It is one thing to announce subsidies and grand industrial acts; it is another to rebuild entire production ecosystems hollowed out over 40 years of offshoring. The United States faces a threefold constraint: time, resources, and knowledge. In terms of time developing new mining, refining, and magnet manufacturing capacity is not a matter of quarters or even years; it’s a decade-long process. Environmental permitting alone can stall U.S. projects for years, while Chinese firms are already vertically integrated and continuously upgrading. As for material resources, even if the U.S. opened every known domestic deposit tomorrow, it still lacks the refining and separation facilities to make those materials usable. Mining without refining simply shifts the bottleneck. Lastly, the US facesknowledge and equipment constraints. China’s near-monopoly on rare earth processing equipment and graphite treatment technology means that even friendly suppliers – Australia, Canada or Brazil – depend on Chinese machinery and expertise. The U.S. does not have the skilled labour force or capital goods base to replicate these processes quickly.

The result is a structural dilemma. No amount of rhetoric or subsidy can compress industrial time. The U.S. can print money, but it cannot print metallurgists, engineers, or processing plants. As I argued in May, the US can keep its dollars; China has the dysprosium.

Ironically, the U.S. has engineered its own isolation. By attempting to exclude China from global technology networks, Washington has incentivised Beijing to constrain the very supply chains the U.S. once took for granted. China, for its part, has pursued a measured escalation strategy; first restricting gallium and germanium exports in 2023, now broadening to rare earth technologies and graphite. Each move demonstrates both restraint and capability: China can choose when, where, and how to tighten the tap.

For the U.S., this is more than an economic inconvenience. It is ageostrategic humiliation. The self-declared arsenal of democracy is now dependent on the industrial capacity of the very nation it sought to cripple.

China’s new controls have revealed the underlying asymmetry of the global economy: one side makes things; the other makes narratives. The real economy of thermodynamics and materials trumps the economy of fictitious capital and simulacra. The U.S. may still dominate finance, media and military power projection, but without access to the materials that make advanced technologies possible, these advantages are increasingly performative.