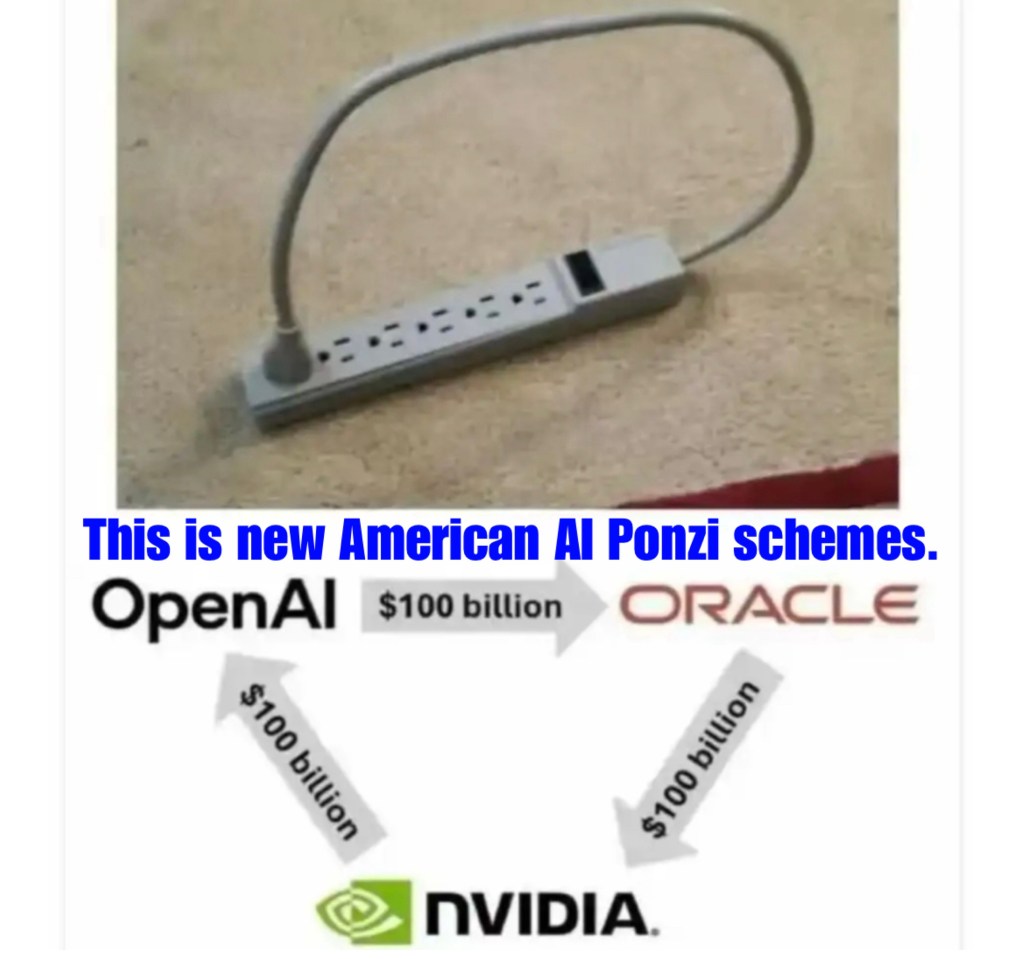

This is new American AI Ponzi schemes. By Johnson Choi 這是美國新版人工智慧龐氏騙局. 作者: 蔡永強 Oct 10 2025

No new value added, they just invest in each others companies created the impression that a bigger pie has been created with the help of news medias like WSJ, Washington Post, CNN, BBC, NYT etc. 他們沒有創造任何新的價值,只是互相投資對方的公司,製造出一種假象,彷彿在《華爾街日報》、《華盛頓郵報》、CNN、BBC、《紐約時報》等新聞媒體的幫助下完成這個騙局!

The AI Ponzi scheme will collapse once investors discovered that 90% of them are losing money. Investors will stop feeding money or buying the stocks. The remaining 10% companies that make money not from AI but on their core business before AI even exists! If you think that is bad enough! Think again! It will also trigger the collapse of the Stablecoin. When the big crash due to happen in next few years, it will make 2008 subprime mortgages Ponzi game world financial crisis nothing in comparison. When it happened and it will happen, don’t expect China to come to your rescue. Those holding US$ and US$ based assets including their US real estate will be wiped out.

一旦投資人發現其中 90% 的公司都在虧損,人工智慧龐氏騙局就會崩潰。投資者將停止投資或購買股票。剩下的 10% 的公司不是從人工智慧賺錢,而是在人工智慧出現之前就透過核心業務賺錢!如果你覺得這已經夠糟了!再想想!這也會引發穩定幣的崩潰。當未來幾年發生大崩盤時,它將使 2008 年次貸龐氏騙局引發的世界金融危機相形見絀。當它發生時,不要指望中國會來拯救你。那些持有美元和美元資產(包括美國房地產)的人將被血本無歸!

When Washington declared an economic war on China’s technology ascent, it assumed it held the upper hand. Tariffs, export bans, entity lists and chip sanctions were meant to isolate Beijing, choke its access to critical inputs, strangle its technological development and protect American primacy. The US believed, actually bragged, at the time, it had stopped China’s technological development in its tracks.

Yet with remarkable precision, Beijing has now demonstrated that the United States is the one more deeply entangled in – and dependent upon – China’s command of critical material supply chains.

Exactly.

China’s latest round of export controls on lithium batteries, graphite anode materials, and rare earth technologies amounts to the most significant intensification yet in the global race for material sovereignty. The measures are framed in terms of “national security,” and necessities to meet China’s obligations to not accelerate arms proliferation. At the same time, the strategic timing and scope make clear their geopolitical intent: to again expose the material vulnerability of a country that has worked tirelessly to encircle, contain and repress China, but which itself cannot easily reconstitute its own productive base.

The new Chinese restrictions announced on 9 October 2025 extend beyond commodities to include the technological processes required to make them useful. This is a deft and also an important expansion of reach from mere resource control to technological chokepoint management.This is actually what the US did to China in terms of chips: not simply the chips themselves, but the tools to design, make them–any foreign manufacturer that had a US component or a US patent somewhere in any of its machinery was constrained from exporting to China. It was as CSIS called it, “4 point chokehold strangling with intent to kill”, “an act of war”. The US is now getting a taste of its own medicine.

In terms of graphite anode materials and lithium batteries, China will now require export permits for synthetic graphite and natural graphite materials used in the production of lithium-ion battery anodes. The restrictions also cover advanced production processes, including granulation, continuous graphitisation, and liquid-phase coating. These are all key technologies that determine battery performance and durability. These technologies are essential for electric vehicles (EVs), consumer electronics and grid-scale energy storage systems. China currently accounts for over 90% of the world’s graphite anode production and dominates every stage of the lithium battery value chain.

As for rare earth-related technologies China has added a sweeping range of rare earth technologies to its export control list, including those involved inmining, smelting, separation, magnetic material manufacturing, and secondary resource recycling. These underpin the manufacture of permanent magnets used in wind turbines, electric motors, guided missile systems, fighter jets, satellite components and semiconductors. China refines nearly 90% of global rare earth oxides and produces the vast majority of neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets used in high-performance electronics.

Together, these measures strike at the heart of the clean energy, defence, and semiconductor industries. In other words, the very sectors the U.S. has spent billions trying to re-shore through the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS Act under the Biden Administration, and which are central to the Trump Administration’s vision for America’s techno-military future. (The focus on clean energy has been dropped.)

According to the Pentagon, over 78% of U.S. military systems rely on materials sourced directly or indirectly from China. Rare earths are used in everything from jet engines and precision-guided munitions to radar systems and nuclear submarine components. A disruption in Chinese supply chains would delay weapons production and maintenance schedules. The U.S. has some rare earth deposits but lacks refining and metallurgical expertise; ironically, these were offshored to China decades ago. Rebuilding domestic refining capacity could take 5–10 years and cost billions, even before environmental approvals and workforce training are considered. Against this backdrop, China’s export restrictions can be seen to be a massive boost to world peace.

While U.S. policymakers focus on lithography and chip design, the less glamorous but critical material inputs – rare earths, gallium, germanium and graphite – remain overwhelmingly Chinese. Rare earth magnets are essential in chip fabrication equipment and data centre cooling systems. Restrictions on graphite and high-purity processing technologies will squeeze the semiconductor value chain from the bottom up, affecting everything from consumer electronics to AI compute clusters. This has wide-ranging implications. Without the rapid expansion of AI capital development in 2025 (data centres and the like), the US GDP growth for the first half of 2025 would have been, according to some estimates, no more than 0.1%. Put another way, the American economy writ large is flaccid at best, and AI-related capex is keeping its head above water. Disruptions to the input supply chains needed by the AI sector will jeopardise the sector’s expansion; it will also increase costs due to supply side disruptions. The impacts of China’s restrictions are double-barrelled: they go to the resources needed for augmenting the US electricity supply sector on the one hand, while also creating bottleneck risks in the supply of semiconductors. The Wall Street AI bubble may well be exposed to the sharp needle of Chinese export restrictions.

The EV revolution in the U.S., if indeed one could even call it that, depends on a Chinese battery ecosystem that dominates both upstream materials and midstream processing. China processes two-thirds of the world’s lithium and over 90% of the world’s graphite. U.S. automakers have only recently begun investing in local cathode and anode production, but the know-how and equipment still come largely from Chinese firms. Supply disruptions will increase EV costs, reduce availability, and slow decarbonisation timelines.

In short, America’s green and digital transitions are built on Chinese foundations. Now those foundations are shifting, or perhaps worse, those foundations have simply been removed.

It is one thing to announce subsidies and grand industrial acts; it is another to rebuild entire production ecosystems hollowed out over 40 years of offshoring. The United States faces a threefold constraint: time, resources, and knowledge. In terms of time developing new mining, refining, and magnet manufacturing capacity is not a matter of quarters or even years; it’s a decade-long process. Environmental permitting alone can stall U.S. projects for years, while Chinese firms are already vertically integrated and continuously upgrading. As for material resources, even if the U.S. opened every known domestic deposit tomorrow, it still lacks the refining and separation facilities to make those materials usable. Mining without refining simply shifts the bottleneck. Lastly, the US facesknowledge and equipment constraints. China’s near-monopoly on rare earth processing equipment and graphite treatment technology means that even friendly suppliers – Australia, Canada or Brazil – depend on Chinese machinery and expertise. The U.S. does not have the skilled labour force or capital goods base to replicate these processes quickly.

The result is a structural dilemma. No amount of rhetoric or subsidy can compress industrial time. The U.S. can print money, but it cannot print metallurgists, engineers, or processing plants. As I argued in May, the US can keep its dollars; China has the dysprosium.

Ironically, the U.S. has engineered its own isolation. By attempting to exclude China from global technology networks, Washington has incentivised Beijing to constrain the very supply chains the U.S. once took for granted. China, for its part, has pursued a measured escalation strategy; first restricting gallium and germanium exports in 2023, now broadening to rare earth technologies and graphite. Each move demonstrates both restraint and capability: China can choose when, where, and how to tighten the tap.

For the U.S., this is more than an economic inconvenience. It is ageostrategic humiliation. The self-declared arsenal of democracy is now dependent on the industrial capacity of the very nation it sought to cripple.

China’s new controls have revealed the underlying asymmetry of the global economy: one side makes things; the other makes narratives. The real economy of thermodynamics and materials trumps the economy of fictitious capital and simulacra. The U.S. may still dominate finance, media and military power projection, but without access to the materials that make advanced technologies possible, these advantages are increasingly performative.