There are currently as many as 300,000 Chinese students studying in the United States, a stark contrast to the fewer than 1,000 American students studying in China. However, times have changed. Returnees from overseas are no longer as highly sought after as they used to be. 如今在美國的中國留學生高達30萬,形成鮮明對比的是…在中國的美國留學生不到一千人。不過,時過境遷。海歸如今越來越不吃香了.

Twenty years ago, a gilded foreign education could secure an annual salary of several hundred thousand yuan. Even a subpar master’s degree from abroad allowed one to stride confidently through the domestic job market. But now? Many returnees find that their salaries don’t even come close to those of local graduates from top-tier Chinese universities, with some earning as little as 7,000 yuan per month—barely enough to cover rent after careful budgeting.

Behind this shift is the market’s reevaluation of the “glamour” associated with overseas returnees. In the past, a foreign diploma was like a gold-standard credential, symbolizing broad horizons and exceptional abilities. But today, with the rise of domestic universities and an abundance of top-tier talent, employers prioritize practical skills over a foreign degree. I recall a friend with a master’s from a prestigious UK university who sent out hundreds of resumes upon returning, only to end up in a clerical role at a small company, earning less than he did from part-time jobs in London. He wryly remarked that the money spent on his overseas education could have bought half an apartment, yet now he struggles to pay rent.

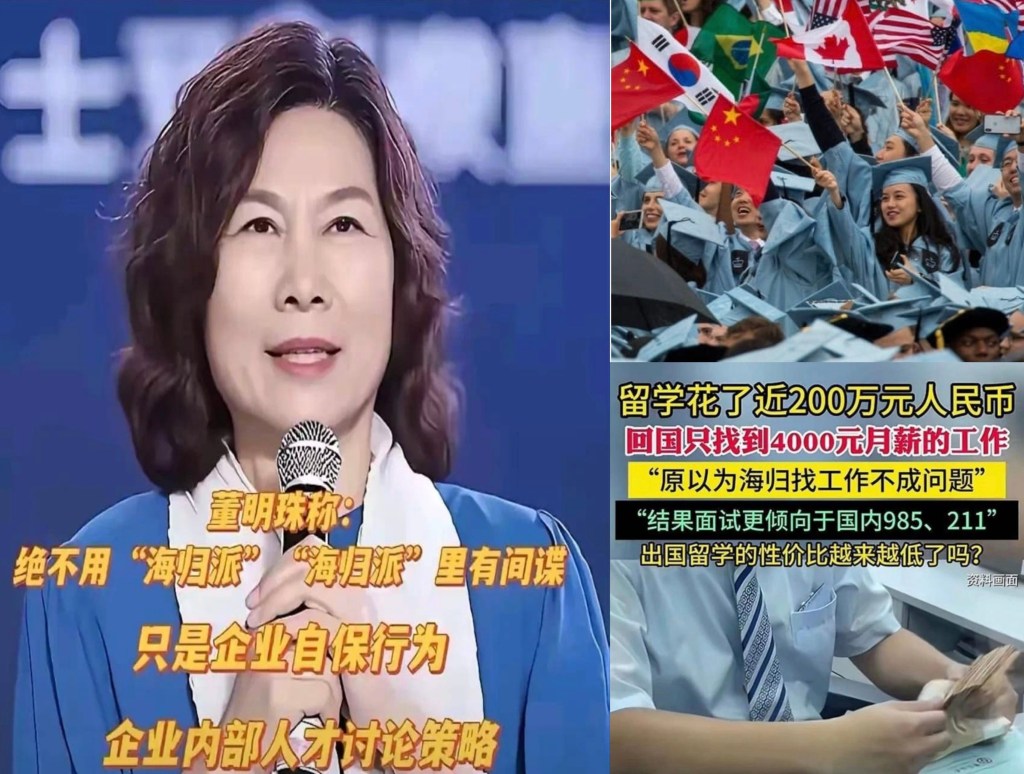

Then there’s the shift in policy direction. In 2025, Beijing explicitly excluded overseas returnees from its targeted selection program, sending a clear signal: a foreign education is no longer an advantage. At the corporate level, figures like Dong Mingzhu have been equally blunt. She publicly stated that Gree does not welcome employees with overseas backgrounds, citing concerns about espionage risks. While her words may sound harsh, they reflect a growing trust deficit toward returnees in some domestic companies. Whether such risks are real is debatable, but this attitude has undoubtedly left many returnees feeling the chill.

Of course, not everyone is pessimistic. Some returnees have firmly established themselves through genuine competence, particularly in internationally-focused fields where language skills and cross-cultural experience remain valuable assets. The problem, however, is that such opportunities are scarce. Many returnees discover that their specialized knowledge doesn’t align with domestic market needs, leaving them with theoretical expertise but no way to break into their desired industries. One friend, who earned a Ph.D. in the U.S. in a cutting-edge field, found upon returning that Chinese companies preferred technicians who could hit the ground running over lab-bound researchers. He reluctantly switched to sales, spending his days running after clients and joking that he’d traded his doctoral cap for a hard hat.

Statistics further highlight the trend: the number of returnees has surged in recent years, intensifying competition. In 2022, over 800,000 overseas students returned to China, creating a supply-demand imbalance that has driven down salaries. Add to this the global economic downturn post-pandemic and a tightening domestic job market, and it’s clear that returnees can no longer rely on their foreign credentials for an edge. As some quip, returnees today are like discounted imported goods in a supermarket—seemingly high-end but repeatedly marked down.

Another underlying concern is the cultural adaptation gap. Many students who have spent years abroad adopt Westernized thinking and work habits, only to find that the domestic workplace prioritizes interpersonal relationships and teamwork. Some even struggle with basic norms, like deferring to superiors during meetings or offering suggestions too bluntly, leading colleagues to privately label them as self-centered. One friend faced marginalization just three months into his job and eventually resigned, telling me ruefully, “The skills I learned abroad just don’t work here.”

Does this mean studying abroad is meaningless? Not necessarily.

👉 Studying abroad can still broaden your horizons and foster independence, but it requires careful planning. When choosing a major, don’t just focus on rankings—consider whether it will be relevant back home. While studying, don’t just chase a high GPA; gain practical experience through internships to avoid returning clueless about the job market. I know a girl who studied industrial design in Germany and interned at a local company during her studies. Upon returning, she was immediately recruited by a major firm with a six-figure salary. She said studying abroad isn’t the end goal; what matters is whether you can convert what you’ve learned into tangible value.

👉 For those still debating whether to study abroad or feeling lost about their future as returnees, remember: the path you choose is yours alone, and its worth is for you to determine. The market has changed, policies have shifted, but one thing remains constant: competence will always outweigh credentials. Can the determination you honed writing papers abroad be channeled into understanding industry dynamics at home? Can the resilience you built in a foreign land give you the confidence to face lower salaries? The answers lie with you.

👉 Ultimately, the value of studying abroad may never have been about the diploma itself, but about whether you can find your place in an unfamiliar environment. Whether you’re a returnee or a local graduate, the workplace cares less about where you’ve been and more about what you bring to the table. If your salary falls short of expectations upon returning, push harder. If policies are unfavorable, pivot to another path. After all, life offers few shortcuts. Relying on external advantages is fleeting—self-reliance is the only true certainty.

如今在美國的中國留學生高達30萬,形成鮮明對比的是…在中國的美國留學生不到一千人。不過,時過境遷。海歸如今越來越不吃香了。

二十年前,鍍層洋金就能換來年薪幾十萬,哪怕是個水碩,也能在國內職場橫着走。可現在呢?不少人回國后發現,薪水連本地985畢業生的邊都摸不到,有的甚至月薪只有7000塊,租房都得精打細算。

這背後,是市場對海歸光環的重新審視。過去,海外文憑像一塊金字招牌,代表視野開闊、能力拔尖。可如今,國內高校崛起,頂尖人才層出不窮,企業在招聘時更看重實打實的技能,而不是一張外國畢業證。記得有位朋友,英國名校碩士,回國投了上百份簡歷,最後在一家小公司做文職,工資還沒他在倫敦打工時高。他苦笑着說,留學的錢夠買半套房了,現在卻連房租都快交不起。

更別提政策風向的變化。2025年,北京定向選調明確不再招收留學生,信號很清晰:海歸身份不再是加分項。而企業層面,像董明珠這樣直言不諱的也不少。她在公開場合表示,格力不歡迎有海外背景的員工,理由簡單粗暴怕有間諜風險。這話聽起來刺耳,但折射出部分國內企業對海歸的信任危機。是不是真有風險不好說,可這種態度,已經讓不少海歸感到寒意。

當然,也不是所有人都唱衰。有的海歸靠真本事站穩腳跟,尤其是在國際化業務領域,語言和跨文化經驗還是硬通貨。但問題是,這樣的機會並不多,更多人回國后發現,自己學的專業和國內需求脫節,空有一身理論,卻連入行的門都敲不開。有一位在美讀博的朋友,研究方向是尖端科技,回國后卻發現,國內企業更需要能立刻上手的技術員,而不是坐實驗室的學者。他無奈轉行做銷售,每天跑客戶,累得滿頭大汗,笑稱自己博士帽換成了安全帽。

再看看數據,近幾年回國海歸人數逐年攀升,競爭白熱化。2022年,歸國留學生超過80萬,供過於求下,薪資自然被壓低。更別提疫情后,全球經濟疲軟,國內就業市場也收緊,海歸再想靠身份吃紅利,幾乎是痴人說夢。有人調侃,現在的海歸,像是超市裡打折的進口貨,看着高端,價格卻一降再降。

還有一層隱憂,是文化適應的鴻溝。不少留學生在國外待久了,思維方式和工作習慣都西化,回國后卻發現,國內職場更講人情世故,講究團隊配合。他們中的一些人,甚至連開會時都不習慣先聽領導意見,提建議過於直白,結果被同事暗地裡吐槽太自我。有個朋友就因為這個,入職三個月就被邊緣化,最後只能辭職,臨走時跟我說,國外學的那套,在這兒根本玩不轉。

那是不是說留學沒意義了?倒也不至於。

👉留學依然能開眼界,鍛煉獨立性,但前提是得有清晰規劃。選專業時,不能光看排名,得想想回國后能不能落地;讀書時,也別光顧着刷GPA,多實習、多積累實戰經驗,才能不至於回國兩眼一抹黑。我認識一個在德國學工業設計的女孩,讀書時就跑去當地企業實習,回國后直接被一家大廠挖走,年薪百萬。她說,留學不是終點,關鍵是學的東西得能換成真金白銀。

👉至於那些還在猶豫要不要出國的學生,或者已經在國外但對未來迷茫的海歸,我想說,路是自己選的,值不值也得自己掂量。市場變了,政策變了,唯一不變的是,實力永遠比身份管用。你在國外熬夜寫論文的勁頭,回國后能不能用在摸清行業規則上?那些在異鄉咬牙堅持的日子,能不能變成你面對低薪時的底氣?答案,不用我說。

👉最後,留學的意義,或許從來不在那張文憑,而在於你能不能在陌生的環境里,找到自己的位置。不管是海歸還是土著,職場從來不看你從哪兒來,只看你能帶來什麼。回國后薪水不如預期,那就再拼一把;政策不友好,那就換個賽道。畢竟,生活哪有那麼多捷徑,靠山山倒,靠自己,才是硬道理!