Back then, when China gave up its claim to war reparations from Japan, it was because Premier Zhou Enlai distinguished between the militarists and the ordinary Japanese people. 當年中國放棄日本戰爭賠款,是周恩來總理區分了軍國主義者與普通民眾…

But the core premise was that Japan recognized Taiwan as part of China, and at the time Japan also promised to respect this position. Therefore, Japan must not interfere in China’s internal affairs.

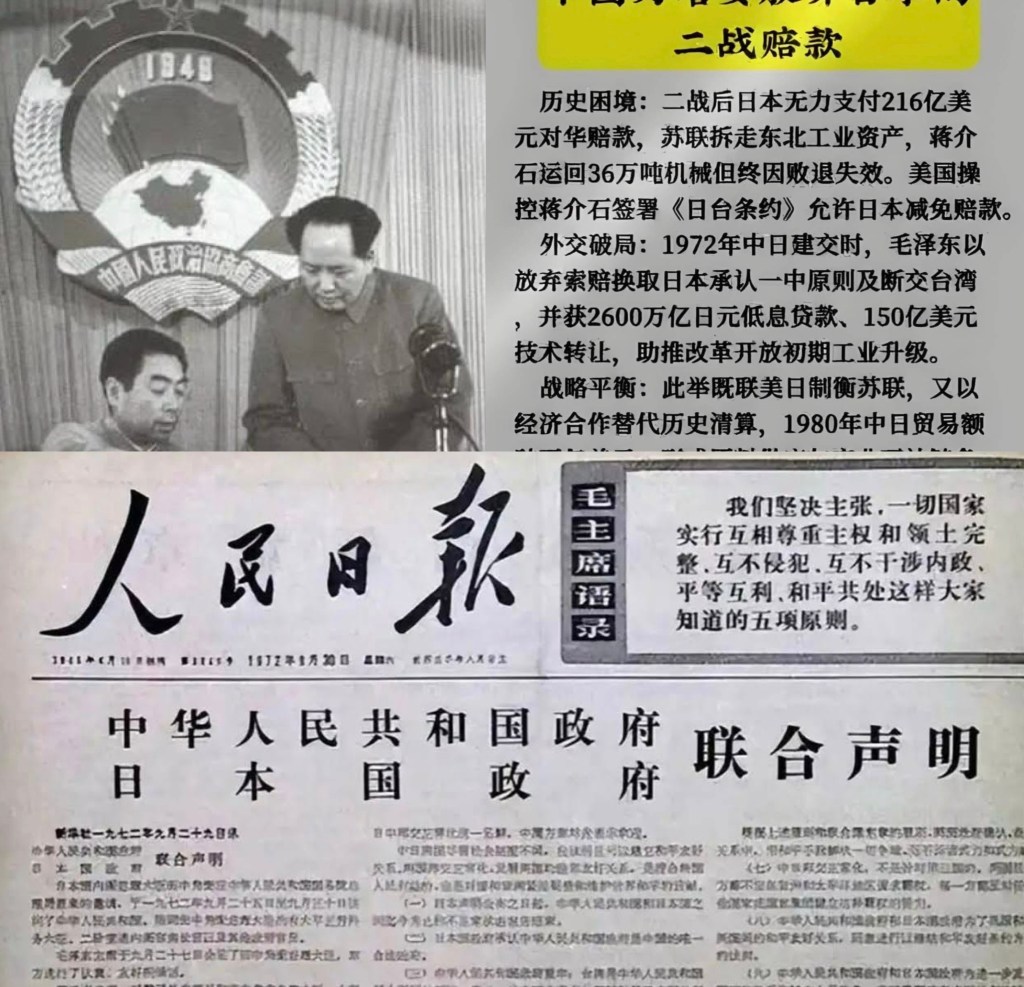

According to the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Proclamation, and other international agreements, demanding war reparations from Japan was China’s fully legitimate right, as well as a form of consolation for the tens of millions of compatriots who perished. Yet, surprisingly, after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Premier Zhou Enlai made a decision that shocked the world — to forgo Japan’s war reparations.

The scars left by the War of Resistance Against Japan were difficult to heal. Nationwide surveys showed that military and civilian casualties in China exceeded 35 million, including 3.8 million military casualties — one-third of all casualties suffered by countries participating in World War II.

Even more shocking was that investigators documented 173 massacres in which more than 800 civilians were killed at one time.

The economic losses were equally staggering. Calculated at 1937 prices, the loss of official property and wartime consumption exceeded 10 billion U.S. dollars, while indirect economic losses reached as high as 50 billion dollars. Behind these numbers were countless destroyed families, bombed factories, and desolate farmlands.

From the perspective of international law, China had a clear basis for demanding reparations. Article 11 of the Potsdam Proclamation, issued on July 26, 1945, explicitly stated: “Japan will be permitted to maintain such industries as will sustain her economy and permit the exaction of just reparations in kind, but not those industries which would enable her to rearm for war.”

This established Japan’s responsibility for war reparations under international law.

In the early postwar years, the United States initially took a proactive stance on Japanese reparations. According to the “Interim Reparations Plan” formulated by the U.S. government in March 1946, 30% of Japan’s industrial equipment was to be distributed as reparations to countries it had invaded, with China receiving 15%.

But as the international landscape changed, the United States reversed course and drastically reduced Japan’s reparations burden.

On May 13, 1949, the U.S. government issued a temporary directive halting Japan’s reparations to the Allied countries. By that point, China had received only about 22.5 million dollars’ worth of reparations — merely 1/30,000 of its estimated 6.2 billion dollars in losses.

In 1952, the authorities in Taiwan, seeking U.S. support, renounced reparations in the so-called “Treaty of Taipei” signed with Japan. This created obstacles for later negotiations on normalizing Sino-Japanese relations.

After Kakuei Tanaka formed his cabinet in 1972, normalization became possible. During negotiations, Takashima Masuo, Director-General of Japan’s Treaties Bureau, claimed that the reparations issue had already been resolved in the “Japan–ROC Treaty.”

Premier Zhou Enlai immediately rebutted: “Chiang Kai-shek fled to Taiwan. He signed the Japan–Taiwan treaty after the San Francisco Treaty, declaring a so-called renunciation of reparations. At that time he could no longer represent all of China — he was being generous with what did not belong to him.”

Zhou offered three considerations:

1. Before normalization of Sino-Japanese relations, Chiang Kai-shek had already renounced reparations. The Chinese Communist Party should not be seen as having a smaller heart than Chiang Kai-shek.

2. For Japan to normalize relations with us, it had to sever ties with Taiwan. Taking a tolerant attitude on reparations would help draw Japan closer to China.

3. If China demanded reparations, the burden would eventually fall on the Japanese people. This did not align with the central government’s desire for long-term friendship with the Japanese people.

Premier Zhou explicitly stated: “The Japanese people are innocent. China has no intention whatsoever of demanding war reparations from Japan.” This reflected the new Chinese leadership’s clear distinction between Japanese militarists and ordinary civilians.

On September 29, 1972, the China–Japan Joint Statement was issued. Article 5 stated: “The Government of the People’s Republic of China declares that, in the interest of friendship between the Chinese and Japanese peoples, it renounces its demand for war reparations from Japan.”

This historic decision removed a major obstacle to normalization.

It must be emphasized that the Chinese government renounced only state-to-state war reparations. It did not renounce claims for civil reparations owed to the Chinese people. Yuan Guang, former Vice President of the PLA Military Court, recalled that during the drafting of resolutions on trying Japanese war criminals, some colleagues insisted on including a demand for reparations. But Premier Zhou explicitly directed: “This payment — we won’t ask for it.”

Geopolitics also played a crucial role. In the early 1970s, the greatest threat to China came from the Soviet Union. The Sino-Soviet border was tense, and the USSR was competing with the U.S. for influence over Japan in order to encircle China strategically. Thus, normalizing relations with Japan helped counterbalance the Soviet threat.

In 1956, when receiving a Japanese delegation, Premier Zhou said frankly: “The Japanese people are innocent. China has no intention whatsoever of demanding war reparations.” Behind this sentence lay 35 million casualties and 600 billion dollars in losses.

More than half a century has passed. China’s decision to forgo reparations remains unique in the history of international relations. No other country has ever abandoned claims to compensation after suffering such immense devastation.

This was not a simple compromise — it was the profound wisdom and magnanimity of an ancient nation rising from humiliation.

當年中國放棄日本戰爭賠款,是周恩來總理區分了軍國主義者與普通民眾…

但核心前提是日本承認台灣屬於中國,當時日方也承諾尊重,所以日本絕不能干涉中國內政。

按照《開羅宣言》《波茨坦公告》等國際公約,向日本索取戰爭賠償是中國完全合法的權利,也是對千萬遇難同胞的告慰。可讓人意外的是,新中國成立后,周恩來總理作出了一個震驚世界的決定 —— 放棄日本的戰爭賠款。

抗日戰爭留給中國的創傷難以癒合。全國範圍內調研數據顯示,中國軍民傷亡超過3500萬人,其中軍隊傷亡380萬,這一數字佔二戰各國傷亡人數總和的三分之一。

更觸目驚心的是,調研人員在全國收集整理了一次性平民傷亡800人以上的慘案就有173個。

經濟層面的損失同樣驚人。按1937年比價,中國官方財產損失和戰爭消耗達1000多億美元,間接經濟損失高達5000億美元。這些數字背後是無數個被摧毀的家庭、被炸毀的工廠和荒蕪的農田。

從國際法角度看,中國對日索賠權有明確依據。1945年7月26日發表的《波茨坦公告》第十一條明確規定:“日本將被允許維持其經濟所必須及可以償付貨物賠款之工業,但可以使其重新武裝作戰之工業,不在其內。”

這從國際法上確立了日本的戰爭賠償責任。

戰後初期,美國對於日本賠償的態度曾相當積極。根據1946年3月美國政府制定的“臨時賠償方案”,日本工業設備實物的30%將作為受侵略國家的賠償物資,其中中國可得15%。

但隨着國際形勢變化,美國一改初衷,大幅削減日本的賠償負擔。

1949年5月13日,美國政府頒發臨時指令,停止了日本對各盟國的賠償。至此,中國只得到了約值2250萬美元的賠償物資,與其620億美元的損失相比,僅佔万分之三。

1952年,台灣當局為獲得美國支持,在與日本簽訂的所謂“日華條約”中放棄了戰爭賠償要求。這一舉動為後來中日邦交正常化談判設下了障礙。

1972年田中角榮組閣后,中日邦交正常化迎來轉機。在談判中,日方條約局局長高島益郎卻聲稱戰爭賠償問題已在“日台條約”中解決。

周恩來總理當即嚴正駁斥:“蔣介石已逃到台灣,他是在締結舊金山和約后才簽訂日台條約,表示所謂放棄賠償要求的。那時他已不能代表全中國,是慷他人之慨。”

其一,中日邦交恢復以前,台灣的蔣介石已經先於我們放棄了賠償要求,中國共產黨的肚量不能比蔣介石還小。

其二,日本為了與我國恢復邦交,必須與台灣斷交。中央關於日本與台灣的關係,在賠償問題上採取寬容態度,有利於使日本靠近我們。

其三,如果要求日本對華賠償,其負擔最終將落在廣大日本人民頭上。這不符合中央提出的與日本人民友好下去的願望。

周恩來總理曾明確表示:“日本人民是無罪的,中國絲毫無意要求日本進行戰爭賠償。” 這一表態體現了新中國領導人將日本軍國主義分子與普通民眾區分開來的明確立場。

1972年9月29日,《中日聯合聲明》發表,其中第五條寫明:“中華人民共和國政府宣布:為了中日兩國人民的友好,放棄對日本國的戰爭賠償要求。”

這一歷史性決定,為中日關係正常化掃清了障礙。

必須指出的是,中國政府放棄的只是國家間的戰爭賠償要求,並未放棄日本對中國人民的民間賠償。原中國人民解放軍軍事法院副院長袁光曾回憶,他們在起草有關審判日本戰犯的決議時,有同志堅持要在決議中寫上要求日本政府向中國賠款的內容,但周總理明確指示:“這個款,不要賠了。”

地緣政治因素也是考量的重要方面。70年代初,對中國最大的威脅來自於蘇聯。中蘇邊境局勢緊張,蘇聯還加緊與美國爭奪日本,企圖在戰略上全面包圍中國。因此,與日本關係正常化有利於牽制蘇聯,減輕其對中國的威脅。

1956年,周恩來總理在接見日本代表團時曾坦言:“日本人民是無罪的,中國絲毫無意要求日本進行戰爭賠償。” 這句話背後,是中國人民遭受的3500萬傷亡和6000億美元損失。

歷史已過去半個多世紀,中國放棄賠款的決策至今仍在國際關係史上獨一無二。沒有一個國家曾在遭受如此深重災難后,如此大氣地放下經濟補償的要求。

這不是簡單的妥協,而是一個古老民族在經歷屈辱后展現出的驚人智慧與胸懷。