I was asked to clarify why my grandfather sets such a strict rules for his offsprings 有人問我,為何祖父對後代訂立如此嚴格的規矩.

Born in 1875, our grandfather entered the world at the twilight of the collapsing Qing Dynasty, in a Hong Kong that was a British colony. Despite those challenging times, he achieved the remarkable feat of gaining entry into an elite school reserved almost exclusively for the white British ruling class. Yet, he refused to become what one might call a “Western moon worshipper”—one who blindly rejects his own heritage. Instead, he critically adopted Western knowledge and values while fiercely insisting that his offspring remain independent and, above all, remember their Chinese roots.

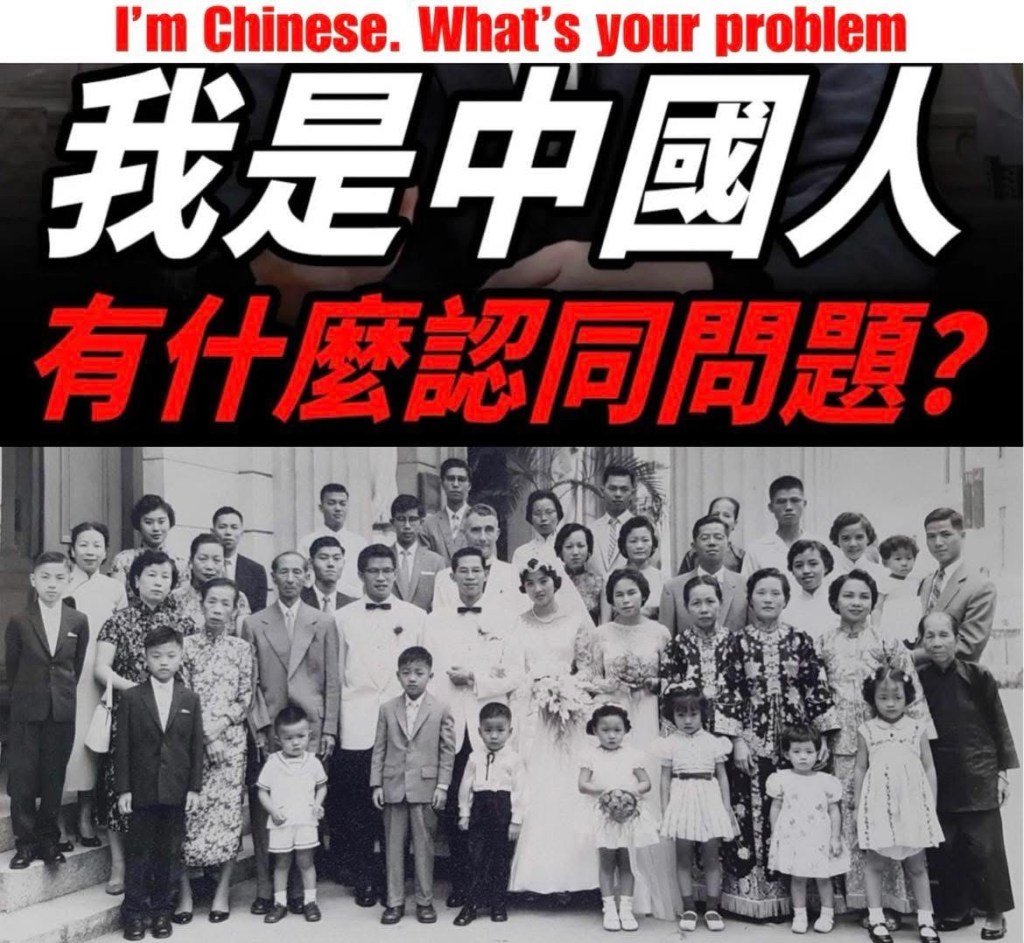

He understood that his high-ranking position at one of the largest British firms, Swire, could grant his children a life of comfort without the need for hard work. To him, such a path was dangerous. He often held the belief that a comfortable life without struggle was like “raising a dog in a greenhouse”; it would lose the resilience needed to survive in the wild and challenging world. We see this echoed today in the West, where many children born into prosperous Chinese families—those of lawyers, doctors, and executives—are raised in such “greenhouses,” often lacking strong work ethics. Worse, many of these parents, themselves ardent admirers of the West, intentionally erase their Chinese heritage from their children’s upbringing. The tragic result is a generation that can no longer identify itself as Chinese.

My grandfather had four children. My father had ten. Imagine if my father had raised his ten in that pampered greenhouse: we could have been ten useless offspring. To prevent this, our grandfather, the true and unwavering authority in our family, worked closely with my father to establish and enforce the Choi family rules. These principles were not about oppression, but about forging character, ensuring that comfort never softened our spirit or severed our roots.

我們的祖父生於1875年,那正是清王朝風雨飄搖的黃昏時分,他降生於英殖民時期的香港。儘管時局艱難,他卻創下非凡成就——考入了一所幾乎專為英國白人統治階層設立的精英學府。然而,他始終拒絕淪為所謂的「崇洋媚外」之人,從不盲目背棄自身文化傳承。相反地,他以批判性眼光吸收西方知識與價值觀,同時堅定要求子女保持獨立人格,並時刻銘記自己的中國根脈。

祖父深知,自己在英資巨擘太古集團擔任的高職,足以讓子女不經奮鬥便享優渥生活。但在他看來,這樣的道路危機四伏。他常言:未經磨礪的安逸生活猶如「溫室養犬」,終將喪失在嚴酷世界中生存所需的韌性。今日西方社會的現象恰印證了他的憂慮——許多出身華裔精英家庭(律師、醫師、企業高管)的子女,在過度庇護的「溫室」中成長,往往缺乏堅毅的品格。更甚者,不少自身痴迷西方文化的父母,刻意在教養中抹去子女的中國文化傳承,最終釀成一代人失去文化認同的悲劇。

祖父育有四名子女,而我的父親則有十個孩子。試想若父親當年將我們置於嬌慣的溫室中養育,我們很可能會成為十個庸碌之輩。為防止這種情況,祖父作為家族中真正堅如磐石的權威,與父親共同制定並嚴格執行了《蔡氏家訓》。這些準則並非壓迫,而是淬鍊品格的砥石,確保安逸永不腐蝕我們的意志,亦不斬斷我們的文化根源。